Select publications

Domestic AI is the New Monstrous-Feminine: Compulsory Roles for Robot-Girls and Women in M3GAN (2023). Cine-Excess Journal, Issue 6, Raising Hell: Demons, Darkness, and the Abject, 2025.

The comedy-horror film M3GAN (Gerard Johnstone, 2023) represents an Artificial Intelligence (AI) doll that a woman tech professional builds to comfort her niece after her parents die. The film went viral before its release via memes of M3gan’s hallway dance: her abject dance moves creepily walk the line between robotic and human. Point of view shots align the doll with Theory of Mind AI: the ability to understand humans’ psychological states and predict their behaviour. Indeed, Gemma is thrilled with her invention precisely because M3gan can care emotionally for her niece, Cady–until the AI doll becomes obsessed with its primary mission. In an attempt to keep Cady safe, M3gan commits gruesome acts of violence. While M3gan’s borderline humanity and violent actions offer the film’s most acute horror, the film’s more insidious horror is our discomfort due to Gemma’s lack of maternal instinct. Drawing on Barbara Creed’s notion of the monstrous-feminine – cinema’s prolific representation of the abject woman-as-monster – I argue that M3GAN illustrates our continued obsession with compulsory motherhood for women and imperative innocence for girls. To nuance this point, I examine the character of Tess, who – within the tradition of Black feminism – critiques Gemma’s maternal outsourcing.

Towards a Transnational Feminist Film Studies Classroom. Teaching Global Media Dossier, edited by Juan Llamas-Rodriguez, JCMS: Journal of Cinema and Media Studies, 2022.

The Western Frontier & American Pulp in la zone: Marcel Carné’s Terrain vague (1960) as Proto-‘Banlieue Film’

JCMS: Journal of Cinema & Media Studies, 2020

This essay examines Marcel Carné’s film Terrain vague (The Wasteland, 1960) as a precursor to post-1980 banlieue (disadvantaged suburbs) genre films due to its representation of the transcultural and postcolonial dimensions of this marginalized space. Carné’s critically disparaged film was produced when US cultural imperialism and the French-Algerian War converged in the metropole. In representing this context, the film presages banlieue film themes and media stereotypes that will intensify in post-1980 France: as the banlieue becomes increasingly racialized, it becomes more troublingly associated with the US ghetto and aberrant virility.

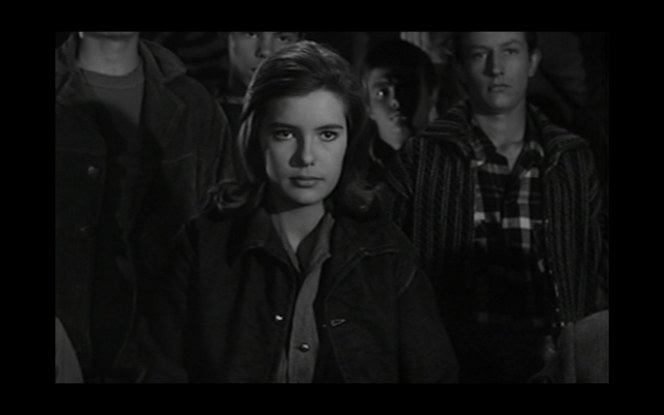

Dan (Danièle Gaubert), a masculine teenage girl, leads the gang in Carné’s Terrain vague (1960) (René Chateau Vidéo)

Truffaut’s L’Enfant sauvage (The Wild Child, 1969): Evoking Autism & the Nascent “Eugenic Atlantic”

Ought: The Journal of Autistic Culture, Dec. 2019.

This essay analyzes François Truffaut’s L’Enfant sauvage (The Wild Child, 1970) as an early representation of autism that metaphorizes the neurodiverse child as the colonial subject. The film takes place in 1798, only a decade after the French Revolution, and depicts the true events of the “wild boy of Aveyron,” a feral child found in the Southern French forest when he was twelve years old. Before the film’s production, Truffaut—who also plays the boy’s teacher, Dr. Jean-Marc Itard—collected articles and books on autism and viewed videos of autistic children to create his main character’s behavioral patterns. The film is thus an exceptionally early representation of autism in narrative film history. While several scholars have analyzed the film with this knowledge—and usually from an autobiographical point of view that uncritically celebrates the film’s auteur director—I merge the critical lenses of disability studies and postcolonial studies to examine it as a white savior film.

Drawing on archival research and considering L’Enfant sauvage’s narrative and production contexts, I explore how the film evokes what Snyder and Mitchell term the “Eugenic Atlantic”—the historical moment when racial and disability eugenics dovetailed at the end of the eighteenth century. The film not only maintains that the boy should be “civilized” in its representation of Itard as the narrative’s hero, but it also conflates disability and race via the following production and formal choices: the casting of a Romani boy (Jean-Pierre Cargol) despite Truffaut’s knowledge that the historical “wild child” was white; and the use of long and iris fade-out shots that work to distance the audience from identifying with the autistic child, most notably in scenes where he connects with nature as he stims (uses repetitive motions to self-stimulate). In its representation of autism-as-savagery only a year after May ’68—a key moment in postcolonial French history—L’Enfant sauvage reveals some of the ways in which colonialism and ableism are mutually imbricated historical methods of normalization that span centuries.

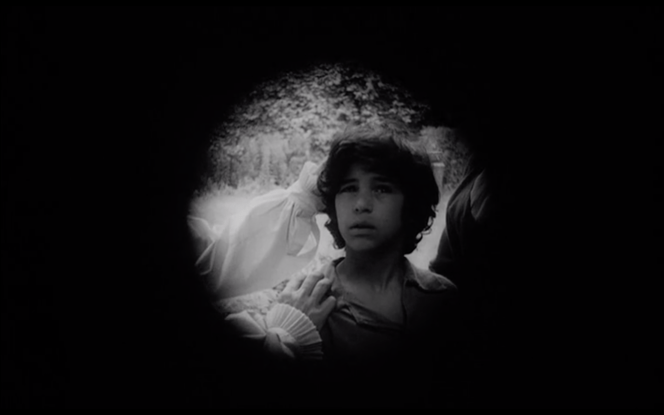

Itard’s (Truffaut) patronizing touch echoes the iris shot–and medical gaze–that constructs Victor (Jean-Pierre Cargol) as abnormal in Truffaut’s L’enfant sauvage (1969) (Les Films du Carrosse)