Sports Movies & Media (Lawrence Tech)

Sexuality in Cinema (Lawrence Tech)

Emotional Outlaws (Course-based Research Experience) (Lawrence Tech)

European Cinema (Lawrence Tech)

Film Genres (Lawrence Tech)

Fall 2020 Courses (Lawrence Tech)

Contemporary Black Literature & Film (GVSU)

This section of Contemporary Black Literature will focus on the topic of Decolonizing Spaces & Bodies. In the first half of the course, we will explore the (post)colonial African context, concentrating on how the process of the European (de)colonization of African nations affected— and continues to affect—the places and people of those nations. In the second half of the course, we will move across the Atlantic Ocean, translating concepts of post-colonial theory to Black experiences and structural racism in the context of a post-Civil Rights Movement United States—while also remembering that these spaces belonged to Native Americans until white Europeans colonized the Americas.

Questions we will reflect on throughout the course include: How do colonists legitimize their violent actions? How does gentrification—as well as the pathologization and fetishization of Black bodies—mimic colonial discourses and actions? How do academic and popular discourses colonize Black thoughts, voices, and spaces? How did African anti-colonial movements and the U.S. Civil Rights Movement begin to de-colonize Black spaces and bodies? How do novelists, poets, activists, filmmakers, and theorists attempt to dismantle power hierarchies that are based on the intersecting social categories of race, ethnicity, socio-economic class, gender, and sexuality?

Queer Studies in Film & TV (Fordham)

This course examines “queer” independent and mainstream film and television. We will delve into classic Hollywood cinema, “New Queer Cinema,” European cinema, “transnational” cinema, as well as U.S. and Canadian television series. We will apply queer, feminist, film, and media theories to the media in order to more profoundly understand our objects of study—the films and TV series themselves—while simultaneously using our objects to better understand the theories and histories. As we unpack assumptions about sexed bodies, sexual desires, gender identities, and sexual identities, we will examine the ways in which films and TV series uphold and subvert the status quo in regards to gender and sexual norms.

Transnational Feminism & Film (SBU)

In their already canonical article on transnational cinema (2011), Will Higbee and Song Hwee Lim maintain that a “critical transnationalism” in film studies should attend to questions of (post)coloniality, power relations, and neocolonialist practices. Yet, while Higbee and Lim call for transnational film studies scholars to engage in interdisciplinary dialogue[1], they fail to adequately address or engage with the pioneering work of many feminist theorists and activists. In 2000, for example, Inderpal Grewal and Caren Kaplan had already defined the transnational paradigm as emerging largely from postcolonial theories. The aim of transnational feminist theories, they write, is to signal “attention to uneven and dissimilar circuits of culture and capital.”[2]

This course brings transnational feminisms and transnational film theories into explicit and productive dialogue. Using these critical lenses, we will analyze select films in terms of (trans)nationalism, (post)colonialism, gender, sexuality, race, ethnicity, language, nationality, religion, and “intersectional”[3] identities/oppressions. Our examination will include Chicana feminisms, Black feminisms, and Muslim feminisms, and we will ask how these practices/theories contribute to transnational theories. Encouraging comparative analyses of transnational processes and their effects, this course places special emphases on various Spanish-language contexts, as well as French-language (post)colonial contexts, from the Algerian War of Independence to the French (trans)nation’s—and the world’s— complicated situation in the present. Shall we be Charlie Hebdo, or not?[4]

[1] Higbee, Will, and Song Hwee Lim. “Concepts of Transnational Cinema: Towards a Critical Transnationalism in Film Studies.” Transnational Cinemas 1.1 (2010): 7-21. Taylor & Francis. Web. 4 April 2014. 18.

[2] Grewal, Inderpal, and Caren Kaplan. “Postcolonial studies and transnational feminist practices.” Jouvert: A Journal of Postcolonial Studies 5.1 (2000). Internet Resource. 5 Sept. 2015 < http://english.chass.ncsu.edu/jouvert/v5i1/grewal.htm>

[3] Crenshaw, Kimberlé. “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence Against Women of Color.” Stanford Law Review 43.6 (1991): 1241-1299. JSTOR. Web. 24 Nov. 2014.

[4] See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charlie_Hebdo

Topics in European Cinema: Crossing National Borders (SBU)

This course focuses on Post-WWII European films that transcend national borders in a variety of ways, including 1) filmmakers who literally cross national borders to make films; 2) films whose makers have been explicitly influenced by films and film movements of other nations; and 3) films whose narratives involve characters who cross or have crossed borders for the purpose of work or tourism. We will look at these films within the context of cultural and political history generally, including the colonial past and (post)colonial present of European nations, and of France, Spain and England in particular. Critical considerations will be given to issues of immigration, exile, mobility, sexuality, identity politics, sex work, nationalism, and the notion of ‘home’.

Questions we will reflect on throughout the course include: Who is free to cross borders, who is forced to cross borders, and who is barred from crossing them – and when? How did films circulate in the post-WWII era, and how have they influenced filmmakers from other nations? How can we differentiate between cultural appropriation and cultural re-inscription or homage? How is border-crossing represented in European cinema, and how does it relate to inequalities stemming from gender, race and socio-economic class? Finally, within the field of Film Studies, how does the term ‘national cinema’ differ from the term ‘transnational cinema’ (or ‘world’ or ‘global cinema’), and how can we use each of these concepts most productively?

Interdisciplinary Study of Film: French Film, Culture, and Power (SBU)

This course examines “French” films and film culture from the beginning of cinematic history through the present day. We will look at this culture within the context of French history more generally, including France’s colonial past and (post)colonial present. We will focus on national memory, as well as issues of power and hierarchy in regards to gender, race and socio-economic class. Directors surveyed include Alice Guy [Blaché], Jean Vigo, Germaine Dulac, Jean Renoir, Agnès Varda, Jean-Luc Godard, Caro & Jeunet, Laurent Cantet, Claire Denis…

This course aims to give students the analytical and critical skills, as well as the cultural and historical context, necessary to discuss and write sophisticatedly on the following questions: How does society influence the films made within that society and vice versa? More specifically: How have certain art, literary, political and social movements influenced film culture? Does film have the power to change society? What is ‘French national cinema’? How does French cinema represent national memory? How do films represent women in society and what is the role of women in the history of French film culture? How are issues of race, gender, class, and (post)colonialism represented in French-language cinema? What roles do the auteur and the cinéphile spectator play in this history? How do the Cinémathèque Française and other film museums, archives, festivals and film magazines contribute to French film culture? Finally, while acknowledging the national and linguistic framework of this course, we will also ask ourselves how we can look at films from other cultural-historical contexts with a productive transnational perspective. That is, how might the dynamics of power and subversion in these films and readings relate to films of other nations and/or languages?

WST 393 summer 2015 Schaefer (SBU)

“Implicit in a feminist politics of affect is the assumption that the association of femininity with affect has led to the simultaneous devalorization of both.” [1]

At first glance, the term “Affect Theory” seems to be an oxymoron, since affect is typically aligned with emotion and the body, while theory is aligned with reason and the mind. This course aims to disturb these assumptions by examining feminist theories of affect and emotion within the humanities and social sciences. We will look at how these theories work to dismantle the following problematic conflations: feminine is emotional is bodily is nature-oriented is backwards is colonized; and masculine is rational is cognitive is culture-producing is progressive is colonizing.

Questions that this course will ask us to reflect on include the following: How have thought and reason come to be identified with the male, Western subject? How have affects, emotions, nature and the body come to be identified with feminine and racial ‘others’? How did feminist activists and scholars begin to dismantle these views—and/or appropriate them for their own means—in the 1970s, 80s, and 90s, and how have feminists continued to do so through the present day? Where do popular discourses stand in regards to these questions? What are “outlaw emotions,”[2] and how do “politically engaged”[3] affect theories differ from other affect theories? How do various theorists define “affect” as opposed (or connected) to “emotion” and “feeling”? How have filmic and other media representations maintained the status quo in regards to gender, race and class stereotypes, and how have films subverted these stereotypes? Is it in our best interest to be “angry feminists” and, as Sara Ahmed claims, to “contest this understanding of emotion as ‘the unthought’, just as we need to contest the assumption that ‘rational thought’ is unemotional”?[4] Does reason always play a part in emotion, and vice versa?

[1] Ann Cvetkovich, Mixed Feelings: Feminism, Mass Culture, and Victorian Sensationalism. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers UP, 1992. 1.

[2] Alison M. Jaggar, “Love and knowledge: Emotion in feminist epistemology.” Inquiry: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Philosophy, 32:2 (1989), 151-176.

[3] Gregory J. Seigworth and Melissa Gregg, “An Inventory of Shimmers.” The Affect Theory Reader. Eds. Melissa Gregg and Gregory J. Seigworth. Durham and London: Duke UP, 2010. 7.

[4] Sara Ahmed, The Cultural Politics of Emotion. Ithaca and London: Cornell UP, 2004. 170.

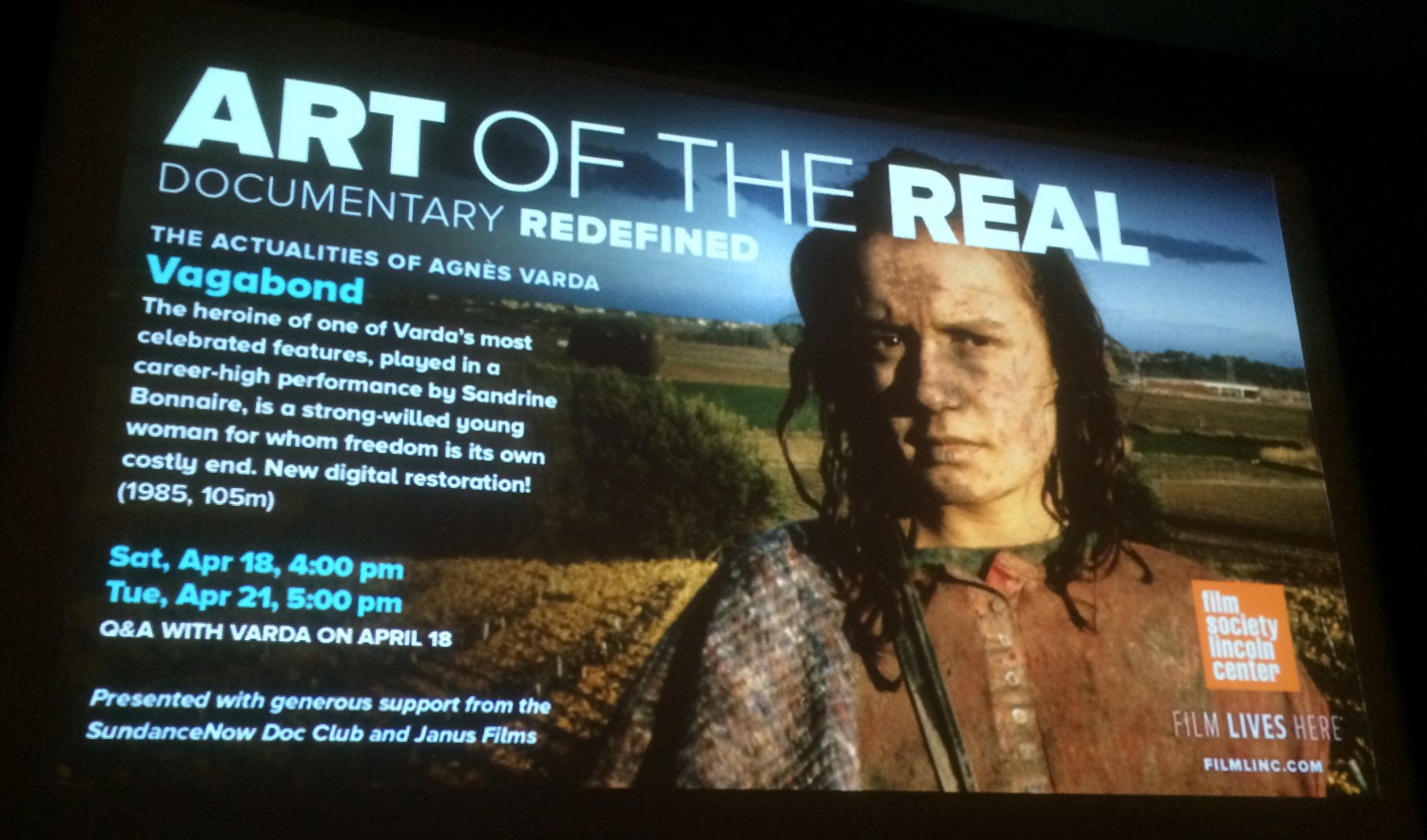

One of the cinematic “emotional outlaws” we studied: Mona Bergeron (Sandrine Bonnaire) in Agnès Varda’s Vagabond (France, 1985), picture taken by Joy C. Schaefer at the “Art of the Real” event at the Film Society of Lincoln Center.